SCOPE OF PROFESSIONAL OBLIGATIONS

PART 1 - CHAPTER 1MATERIAL SCOPE OF APPLICATION

In order to determine whether a professional is required to lodge a suspected money laundering report, it is necessary to know in advance the offences the object or proceeds of which may give rise to a money laundering offence, but without necessarily circumscribing the offence (Section 1: Predicate offences).

The transposition into Luxembourg law of Directive (EU) 2018/1673 aimed at combating money laundering by means of criminal law will see the offence of money laundering extended to all crimes and offences.

Over and above the scope of application of Luxembourg law to certain categories of offences, professionals must in addition take account, in the context of cross-border activities, of the criminal law of the host country (Section 2: Risks connected with the cross-border transaction of banking and financial business).

Section 1. Money laundering and terrorist financing offences

1.Predicate offences

Article 506-1 of the Penal Code contains a list of predicate offences, made up of two parts: first, offences expressly designated as predicate offences, and second, an “open-ended” list defined according to a penalty threshold and including all offences punishable by a minimum term of imprisonment of more than six months.

This approach corresponds to Recommendation 3 (money laundering offence) and 5 (terrorist financing offence) of the FATF:

“Predicate offences may be described by reference to … a threshold linked either to a category of serious offences; or to the penalty of imprisonment applicable to the predicate offence (threshold approach); or to a list of predicate offences; or a combination of these approaches.”

“The concept of primary offence refers to all offences covered by Article 506-1 of the Penal Code. This list includes most of the serious offences contained in the Penal Code (for example bankruptcy, corruption, kidnapping, sexual exploitation, forgery, fraud, murder, human trafficking, theft, etc.) or contained in special acts of legislation (for example counterfeiting, criminal tax offences, environmental offences, trafficking of illicit narcotics and psychotropic substances, etc.)”.

Money laundering offences are also punishable where the predicate offence has been committed abroad. However, that offence must be punishable in the State where it has been committed.

2. The elements constituting the offence of money laundering

The offence of money laundering as laid down in Article 506-1 of the Penal Code, being a statutory offence, can only be found by a criminal court to have been committed if it is co-existent both with a material (substantive) element and an element of intent.

2.1 The material element

The material element corresponds to the materialisation of an act or behaviour which will ultimately result in the act of money laundering. The Guideline of the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) entitled “Suspicious operations report” sets out the three types of behaviour characterising money laundering offences:

“The offence of money laundering and associated predicate offences, defined in Article 506-1 of the Penal Code and Article 8 (1) (a) and (b) of the Law of 19 February 1973, as amended, on the sale of medicinal substances and measures to combat drug addiction, covers three different types of behaviour:

- those who knowingly facilitated, by any means, the misleading justification of the nature, origin, location, availability, movement or ownership of property, which are referred to in section 31, paragraph 2 (1) and which constitute the direct or indirect purpose or product of one or more primary offences or which constitute any kind of patrimonial benefit, resulting from one or more of those offences,

- those who knowingly assisted in the placement, concealment, disguise, transfer or conversion of property, which are referred to in section 31, paragraph 2 (1) and which constitute the direct or indirect purpose or product of one or more primary offences or which constitute any kind of patrimonial benefit, resulting from one or more of those offences,

- those who have acquired, held or used property, which are referred to in section 31, paragraph 2 (1) and which constitute the direct or indirect purpose or product of one or more primary offences or which constitute any kind of patrimonial benefit, resulting from one or more of those offences.”

“Money laundering consists of any act relating to the proceeds or the object i.e. to any economic benefit drawn from the predicate offence. The legal definition of money laundering is very broad and encompasses a whole set of devices which all serve the purpose to provide a false justification of the origin of the property forming the object or proceeds of the predicate offences.”

2.2 The element of intent

The element of intent is a decisive factor for the commission of the offence of money laundering. Thus, any person who has “knowingly” committed a criminal act referred to in Article 506‑1 of the Penal Code, combined with the material element, will bring about the commission of the offence of money laundering. The person committing the act therefore knows that the funds used derive from an unlawful activity.

Judgment No 14/1 of the Cour d’Appel (Court of Appeal), Criminal Chamber, of 29 March 2017: proof of knowledge of the fraudulent origin of funds is derived from a body of evidence from which it may be concluded that the accused could not have been unaware of the existence of fraud, or must necessarily have known of the fraudulent origin thereof.

Even though a professional is not required to categorise the predicate offence when submitting a suspicious operation report to the FIU, it is a precondition of any reporting initiative that the professional must know the different types of predicate offences in respect of money laundering as set out in Annex II.

The professional submitting the report must do so on the website ‟goAML” (see https://justice.public.lu/fr/organisation-justice/crf.html) referring also to the instructions concerning the reporting formalities given by the FIU in its Guideline entitled “Suspicious operations report” (see the tab entitled “Documents” below the link https://justice.public.lu/fr/organisation-justice/crf.html).

Professionals submitting reports may configure their IT system in such a way as to export relevant information directly in a computerised file. That XML file – which must be in strict conformity with the technical requirements imposed by the FIU– may be downloaded in the form of a report (see https://faq.goaml.lu/manuels-dutilisation/faire-une-declaration/telecharger-fichier-xml).

The FIU encourages all professionals to lodge suspicious operations reports via the goAML tool, which enables it to gather invaluable information and data in the exercise of its prerogatives, even where it does not revert to the professionals concerned.

For the answers to all questions regarding the goAML tool, please refer to be the latter’s instruction manuals, available via the following link: FAQ goAML

Moreover, professionals are welcome to contact the FIU direct by telephone (+352 47 59 81-447), or e-mail at crf@justice.etat.lu

3. Elements specific to certain predicate offences

3.1 The offence of terrorist financing

“The offence of terrorist financing, defined in Article 135-5 of the Penal Code, is ‘the act of providing or collecting, by any means, directly or indirectly, unlawfully and intentionally, funds, assets, or properties of any nature, with a view to utilising them or knowing that they will be utilised, partly or in whole, for the purpose of committing or attempting to commit one or more of the offences referred to in paragraph (2) of the present Article (see Annex II), even if they have not actually been used to commit or attempt to commit any of these offences or if they are not related to one or more specific terrorist acts’.”

“The term ‘funds’ includes assets of any kind, whether tangible or intangible, comprising moveable or immoveable property, acquired by whatever means, and documents or legal instruments in whatever form, including electronic or digital form, showing a right of ownership of, or an interest in, such assets or in any bank credits, traveller’s cheques, bank cheques, money orders, shares, securities, bonds, drafts and letters of credit, without this list being exhaustive”.

Recommendation 5 of the FATF thus states that terrorist financing includes financing the travel of individuals who travel to a State other than their States of residence or nationality for the purpose of the perpetration, planning, or preparation of, or participation in, terrorist acts or the providing or receiving of terrorist training.

3.2 Tax crimes

The Fourth Anti-Money Laundering Directive includes, in the definition of “criminal activity” which may give rise to money laundering, the following:

“All offences, including tax crimes relating to direct taxes and indirect taxes, (…) which are punishable by deprivation of liberty or a detention order for a maximum of more than one year or, as regards Member States that have a minimum threshold for offences in their legal system, all offences punishable by deprivation of liberty or a detention order for a minimum of more than six months”.

That provision was transposed into Luxembourg law by the Law of 23 December 2016, which introduces two new offences in the list of predicate offences relating to money laundering:

- aggravated tax fraud, which is defined according to the tax thresholds evaded or the level of reimbursement obtained;

- tax evasion, the increased gravity of which is due not only to the amounts involved but also to the fact that means have been employed with a view to deceiving the tax authorities.

The offences of aggravated tax fraud and tax evasion relate both to direct taxes (income taxes, registration fees, inheritance taxes, etc.) and to indirect taxes (VAT).

The offence of money laundering is punishable in respect of the predicate offences of aggravated tax fraud and tax evasion committed as from 1 January 2017.

CSSF Circular 17/650 contains in particular, in Annex I, a list of indicators likely to reveal potential laundering of a predicate tax offence, to which professionals may usefully refer. It should be noted that the presence of an indicator does not in itself justify any conclusion that a predicate tax offence has been committed. A new list of indicators specific to collective investment activities was introduced on July 3, 2020 in CSSF Circular 20/744 (see appendix 2).

Although professionals are not required to specify the predicate offence when lodging a suspicious operations report with the FIU (see Article 5 (1) (a) of the Law), they should be aware of the applicable thresholds needing to be exceeded for the purposes of commission of the predicate tax offences in question.

In the case of a customer resident in Luxembourg for tax purposes, the thresholds applicable to the offences in question are as follows:

“Any person who fraudulently evades or attempts to evade payment of all or any taxes, duties and levies the collection of which is the responsibility of the Administration de l’enregistrement et des domaines apart from value added tax shall, where the fraud thus committed or attempted relates, per reporting period or triggering event, to an amount exceeding one quarter of the duties due, being not less than 10 000 euros or an amount exceeding 200 000 euros, be liable to punishment, for aggravated tax fraud, in the form of imprisonment for a term of between one month and three years and a fine of between 25 000 euros and an amount equal to six times the amount of the duties evaded.

If the person concerned has systematically used fraudulent acts with a view to concealing pertinent facts from the tax authorities or persuading them that inaccurate information is correct, and if such committed or attempted fraud relates, per reporting period or triggering event, to a significant amount, either in absolute terms or in relation to the duties due, the perpetrator shall be liable to punishment, for tax evasion, in the form of imprisonment for a term of between one month and five years and a fine of between 25 000 euros and an amount equal to ten times the amount of the duties evaded.”

By contrast, the Luxembourg reporting thresholds are not applicable to non-residents, in respect of whom any potential suspicion should be reported, as the case may be, as from the very first euro, it being understood that the thresholds will vary depending on the customer’s tax residence.

However, money laundering is punishable in Luxembourg only if the offence is also a predicate offence in the country where the customer is resident, in accordance with the principle that the offence in question constitutes an offence in both countries.

4. From the original suspicion to the reporting of a suspicious operation

The obligation to cooperate with the authorities (Chapter 7) requires professionals to “inform the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) promptly, on their own initiative, (…) when they know, suspect or have reasonable grounds to suspect that money laundering, an associated predicate offence or terrorist financing is being committed or has been committed or attempted (…)”.

That obligation is such that the idea of a suspicion must exist as a precondition for proceeding, as the case may be, to submit a report to the FIU.

4.1 The notion of suspicion

The FIU defines suspicion as “(…) a negative opinion of someone or of his/her behaviour, based on hints, impressions, intuitions, but without any specific evidence. This means that, when reporting a suspicion, no evidence of money laundering, an associated predicate offence or terrorist financing is required. All that is needed are circumstances which would make such a hypothesis likely”.

“The terms ‘suspect’ or ‘have reasonable grounds for suspecting’ mean that the financial institution must treat the funds involved, the operation concerned or the act in question as suspect where, in accordance with its vigilance obligations and in light of its analysis of the information gathered by it, it is prompted to harbour a suspicion (‘suspect’), or where the circumstances include elements which do not allow it reasonably to dismiss all doubt (‘have reasonable grounds for suspecting’), regarding the lawfulness of the origin of the funds or of the operation, or regarding their economic, legal or fiscal justification”.

“The determination of the suspicion must be the fruit of a process of intellectual reasoning and duly substantiated analysis. It cannot be carried out by means of automated systems alone, but instead requires human intervention founded on an analysis of the atypical facts and operations and the circumstances thereof, in order to decide whether those atypical facts or operations are likely to be linked to money laundering/terrorist financing and must therefore be the subject of a report to the FIU or conversely to conclude, on the basis of that analysis, that such suspicions can be dismissed and that the matter is to be closed without any further action being taken.”

4.2 The origins of the suspicion

The professional may suspect, or have reasonable grounds for suspecting, that money laundering is going on, “(…) in particular in consideration of the person concerned, its development, the origin of the funds, or the purpose, nature and procedure of the operation”.

“(…) Reporting a suspicious transaction has no minimum monetary threshold. Several factors should be taken into account, which individually may seem irrelevant, but can generate doubts on the veracity of the operation when combined. In general, when a transaction or financial operation, whether only attempted or already executed, raises questions (from the professional) or raises a feeling of discomfort, worry or suspicion, it could potentially be linked to money laundering, an associated predicate offence or terrorism financing.”

It is best to use indicators that could reveal a possible link to money laundering, an associated predicate offence or terrorism financing. The report forms on goAML Web give three sets of indicators related (1) to the person of the customer or prospective customer, (2) to the operations or transactions, and (3) to the behaviour and profile of the customer or prospective customer.

4.3 Examples of suspected money laundering

The FIU has drawn up examples of indicators linked to the customer as a person, to an operation/transaction and to the customer’s behaviour/profile, relating to particular situations.

The indicators linked to the customer correspond, for example, to:

– criminal records or possession of the status of a PEP;

– suspicious or atypical behaviour;

– reluctance to hand over supporting documents;

– barely credible evidence of the origin of the customer’s assets;

– insistence on the speedy opening of an account.

Professionals are invited to draw up a list of non-exhaustive list of criteria which will give rise to suspicions on their part.

The indicators linked to an operation or transaction are multi-faceted.

“The suspicion can arise from the fact that the operation or transaction in question is the consequence of fraudulent behaviour, from the frequency of the transaction or operation, from the amount in question, from the unusual use of certain means of payment, from the interference of certain persons, natural or legal, from an act executed by a non-regulated financial intermediary, from the identity of the recipient of the funds or from the price used. The combination of several of these indicators increases the likelihood that money laundering, an associated predicate offence or terrorist financing is being committed.”

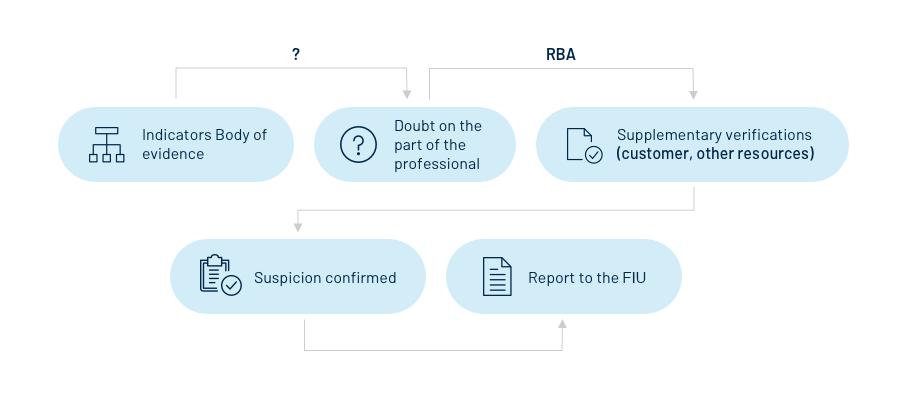

4.4 Summary of the reporting process

The process of submitting a report to the FIU may be summarised as follows:

The starting point of the period for reporting suspicious transactions to the financial intelligence unit begins as soon as the professional concludes that a residual doubt remains about the prospect / client or the transaction, confirming the suspicion. This is how the professional’s obligation to report “without delay” to the financial intelligence unit is understood.

If the professional considers, given the complexity of the case, that it will not be possible for him to complete his declaration in due form on time, it is recommended to proceed in two stages:

(i) by first sending the financial intelligence unit a short statement with enough elements to enable it to make a decision on a possible blocking

(ii) then an additional declaration to be made as soon as possible to provide additional information.

Exceptionally, in matters of terrorist financing, with regard to preventing a serious danger, the professional will contact the financial intelligence unit by telephone in parallel with the declaration by goAML.

Section 2. Risks linked with the cross-border transaction of banking and financial business

In the context of cross-border business, the legal classification of facts and acts as categorised under foreign laws, which may differ from that under Luxembourg law, may involve enhanced legal risks, notably of a criminal and regulatory nature.

“Member States should ensure that there are no obstacles to carrying out activities receiving mutual recognition in the same manner as in the home Member State, provided that the latter do not conflict with legal provisions protecting the general good in the host Member State.”

“(…) professionals, their dirigeants (executives) and employees are required, on their own initiative, promptly to provide information to the FIU (…)”

The obligation to report suspicious operations incumbent on an institution incorporated under foreign law operating pursuant to its freedom to provide services (FPS) in Luxembourg or via a Luxembourg branch is determined in accordance with Luxembourg law, which means that reports concerning suspected money laundering are to be submitted to the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU).

“(…) the notion of a professional also covers branches in Luxembourg of foreign professionals as well as professionals incorporated under foreign law providing services in Luxembourg without setting up a branch in Luxembourg.”

The cross-border transaction of banking business concerns two distinct situations:

- professionals established in Luxembourg exercising their freedom to provide services (“FPS”) in other European Union Member States;

- professionals established abroad operating on Luxembourg territory in the exercise of their FPS or having a branch in Luxembourg.

Professionals operating from Luxembourg in the exercise of their FPS are advised to acquaint themselves in advance of the statutory and regulatory provisions applicable in the territory of the host country/countries (being, inter alia, public order interest rules and overriding mandatory provisions) and their potential impact on the cross-border activities developed.

Professionals operating from or towards Luxembourg in the exercise of their FPS are bound not only to respect the rules designed to combat money laundering in their home country but also to take account of the criminal law and all general public interest rules in the host country.

Indeed, they could find that they are guilty of an offence against the rules laid down by the criminal anti-money laundering laws in the host country, and they must bear in mind that those laws, taken as a whole, encompass all behaviour likely to generate a profit, in so far as such behaviour contravenes the laws in question.

N.B. The Cour d’Appel, in its judgment of 3 June 2009, held that, “if necessary or appropriate in accordance with the second paragraph of Article 506-3 of the Penal Code, save in the case of offences for which the law allows a prosecution even though they are not punishable in the State where they have been committed, where the predicate offence has been committed abroad, whether or not it is punishable in the State where it has been committed, its categorisation depends on the Luxembourg law as applied by the court seised of the money laundering offence and not on the law of the State where it was committed”.

Professionals operating in the exercise of their FPS are invited to consult the list of supervisory authorities for the financial sector in the 28 Member States as drawn up by the European Banking Authority or the European Securities and Markets Authority.

They may also find it useful to refer to the dedicated sections contained in those authorities’ websites, compiling the relevant information regarding the legal framework in relation to financial crime, for example:

– the website of the Belgian FSMA;

– the website of the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority;

– the website of the German BAFIN