Preface

This document forms part of the ABBL’s action plan to fight money laundering, and is designed to bring its members up to the mark in meeting the requirements involved in combatting money laundering and terrorist financing, whilst at the same time helping to enhance Luxembourg’s image as a financial market-place.

For the purposes of this document, the expression “combatting money laundering” is used to cover not only the fight against money laundering in the strict sense of the term but also the fight against terrorist financing and the unlawful proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, known for short as AML/CFT.

Effective participation by credit institutions and other financial sector professionals in the fight against money laundering presupposes, and is dependent on, a thorough knowledge of the applicable legislation and regulations.

This document is intended to assist them in the effective performance of their obligations, in accordance with the statutory and regulatory provisions applicable in the matter, and to provide various details regarding the practical implementation of the legislation. ABBL is not hereby seeking to impose new professional obligations on credit institutions and other financial sector professionals, or to interpret the legal rules.

Preventing financial channels from being used for money laundering is a top priority, and the players in the financial market-place are cooperating with a view to the application of measures adopted at both national and international levels. In so doing, and in the application of the relevant rules, it is important to ensure that the steps taken strike the right balance between, on the one hand, extreme vigilance with regard to banking and financial operations which could prove to be suspect and, on the other hand, respect for privacy. Whilst the risk of the system being used for money laundering purposes should not be underestimated, it should not be overestimated either. A targeted approach to the real risk needs to be adopted by each and every financial sector professional. That approach must be based on a good knowledge of the level of risk involved and suitable adaptation of the professional’s internal procedures.

The Law of 5 April 1993 on the financial sector, as amended, and the Law of 12 November 2004 on the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing, as amended, (“the Law”) impose stringent requirements as regards combatting money laundering on, inter alia, credit institutions and the other financial sector professionals (FSPs). For the purposes of this document, the term “professional” is used without distinction to signify credit institutions and other financial sector professionals.

Under Article 39 of the Law of 5 April 1993 on the financial sector, as amended in particular by the Law of 13 February 2018, such institutions and other professionals are in essence subject, in the fight against money laundering, to three professional obligations, namely the obligation to know one’s customers, the obligation to have an adequate internal organisation and the obligation to cooperate with the authorities.

The first part of this document is devoted to an examination of certain particular aspects relating to the predicate offences on which money laundering is based and the material and personal scope of application of the relevant professional obligations. The second part deals with the content of those professional obligations, and the best practices identified to provide professionals with guidance in the implementation of the rules.

Since the Recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force (“FATF”) constitute the international standard on combatting money laundering and the financing of terrorism, a correlation table showing the equivalences between those recommendations and the structure of this AML Handbook appears in Annex I.

This AML Handbook is not intended to provide legal advice and has no normative value. Its aim is, in particular, to make it easier to follow the legal framework of AML/CFT on the basis of the interpretations, understanding and hypotheses accepted by financial actors.

Whilst every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained in this AML Handbook is pertinent and up-to-date as at the time of its publication, that information is not exhaustive.

Thus, the content of this document may change in line with the laws and regulations enacted and adopted and, as the case may be, any updates and clarifications issued by the CSSF, in the light of which this AML Handbook may be updated and supplemented in the future.

Using the interactive handbook

MATERIAL SCOPE OF APPLICATION

In order to determine whether a professional is required to lodge a suspected money laundering report, it is necessary to know in advance the offences the object or proceeds of which may give rise to a money laundering offence, but without necessarily circumscribing the offence (Section 1: Predicate offences).

The transposition into Luxembourg law of Directive (EU) 2018/1673 aimed at combating money laundering by means of criminal law will see the offence of money laundering extended to all crimes and offences.

Over and above the scope of application of Luxembourg law to certain categories of offences, professionals must in addition take account, in the context of cross-border activities, of the criminal law of the host country (Section 2: Risks connected with the cross-border transaction of banking and financial business).

Section 1. Money laundering and terrorist financing offences

1.Predicate offences

Article 506-1 of the Penal Code contains a list of predicate offences, made up of two parts: first, offences expressly designated as predicate offences, and second, an “open-ended” list defined according to a penalty threshold and including all offences punishable by a minimum term of imprisonment of more than six months.

This approach corresponds to Recommendation 3 (money laundering offence) and 5 (terrorist financing offence) of the FATF:

“Predicate offences may be described by reference to … a threshold linked either to a category of serious offences; or to the penalty of imprisonment applicable to the predicate offence (threshold approach); or to a list of predicate offences; or a combination of these approaches.”

“The concept of primary offence refers to all offences covered by Article 506-1 of the Penal Code. This list includes most of the serious offences contained in the Penal Code (for example bankruptcy, corruption, kidnapping, sexual exploitation, forgery, fraud, murder, human trafficking, theft, etc.) or contained in special acts of legislation (for example counterfeiting, criminal tax offences, environmental offences, trafficking of illicit narcotics and psychotropic substances, etc.)”.

Money laundering offences are also punishable where the predicate offence has been committed abroad. However, that offence must be punishable in the State where it has been committed.

2. The elements constituting the offence of money laundering

The offence of money laundering as laid down in Article 506-1 of the Penal Code, being a statutory offence, can only be found by a criminal court to have been committed if it is co-existent both with a material (substantive) element and an element of intent.

2.1 The material element

The material element corresponds to the materialisation of an act or behaviour which will ultimately result in the act of money laundering. The Guideline of the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) entitled “Suspicious operations report” sets out the three types of behaviour characterising money laundering offences:

“The offence of money laundering and associated predicate offences, defined in Article 506-1 of the Penal Code and Article 8 (1) (a) and (b) of the Law of 19 February 1973, as amended, on the sale of medicinal substances and measures to combat drug addiction, covers three different types of behaviour:

- those who knowingly facilitated, by any means, the misleading justification of the nature, origin, location, availability, movement or ownership of property, which are referred to in section 31, paragraph 2 (1) and which constitute the direct or indirect purpose or product of one or more primary offences or which constitute any kind of patrimonial benefit, resulting from one or more of those offences,

- those who knowingly assisted in the placement, concealment, disguise, transfer or conversion of property, which are referred to in section 31, paragraph 2 (1) and which constitute the direct or indirect purpose or product of one or more primary offences or which constitute any kind of patrimonial benefit, resulting from one or more of those offences,

- those who have acquired, held or used property, which are referred to in section 31, paragraph 2 (1) and which constitute the direct or indirect purpose or product of one or more primary offences or which constitute any kind of patrimonial benefit, resulting from one or more of those offences.”

“Money laundering consists of any act relating to the proceeds or the object i.e. to any economic benefit drawn from the predicate offence. The legal definition of money laundering is very broad and encompasses a whole set of devices which all serve the purpose to provide a false justification of the origin of the property forming the object or proceeds of the predicate offences.”

2.2 The element of intent

The element of intent is a decisive factor for the commission of the offence of money laundering. Thus, any person who has “knowingly” committed a criminal act referred to in Article 506‑1 of the Penal Code, combined with the material element, will bring about the commission of the offence of money laundering. The person committing the act therefore knows that the funds used derive from an unlawful activity.

Judgment No 14/1 of the Cour d’Appel (Court of Appeal), Criminal Chamber, of 29 March 2017: proof of knowledge of the fraudulent origin of funds is derived from a body of evidence from which it may be concluded that the accused could not have been unaware of the existence of fraud, or must necessarily have known of the fraudulent origin thereof.

Even though a professional is not required to categorise the predicate offence when submitting a suspicious operation report to the FIU, it is a precondition of any reporting initiative that the professional must know the different types of predicate offences in respect of money laundering as set out in Annex II.

The professional submitting the report must do so on the website ‟goAML” (see https://justice.public.lu/fr/organisation-justice/crf.html) referring also to the instructions concerning the reporting formalities given by the FIU in its Guideline entitled “Suspicious operations report” (see the tab entitled “Documents” below the link https://justice.public.lu/fr/organisation-justice/crf.html).

Professionals submitting reports may configure their IT system in such a way as to export relevant information directly in a computerised file. That XML file – which must be in strict conformity with the technical requirements imposed by the FIU– may be downloaded in the form of a report (see https://faq.goaml.lu/manuels-dutilisation/faire-une-declaration/telecharger-fichier-xml).

The FIU encourages all professionals to lodge suspicious operations reports via the goAML tool, which enables it to gather invaluable information and data in the exercise of its prerogatives, even where it does not revert to the professionals concerned.

For the answers to all questions regarding the goAML tool, please refer to be the latter’s instruction manuals, available via the following link: FAQ goAML

Moreover, professionals are welcome to contact the FIU direct by telephone (+352 47 59 81-447), or e-mail at crf@justice.etat.lu

3. Elements specific to certain predicate offences

3.1 The offence of terrorist financing

“The offence of terrorist financing, defined in Article 135-5 of the Penal Code, is ‘the act of providing or collecting, by any means, directly or indirectly, unlawfully and intentionally, funds, assets, or properties of any nature, with a view to utilising them or knowing that they will be utilised, partly or in whole, for the purpose of committing or attempting to commit one or more of the offences referred to in paragraph (2) of the present Article (see Annex II), even if they have not actually been used to commit or attempt to commit any of these offences or if they are not related to one or more specific terrorist acts’.”

“The term ‘funds’ includes assets of any kind, whether tangible or intangible, comprising moveable or immoveable property, acquired by whatever means, and documents or legal instruments in whatever form, including electronic or digital form, showing a right of ownership of, or an interest in, such assets or in any bank credits, traveller’s cheques, bank cheques, money orders, shares, securities, bonds, drafts and letters of credit, without this list being exhaustive”.

Recommendation 5 of the FATF thus states that terrorist financing includes financing the travel of individuals who travel to a State other than their States of residence or nationality for the purpose of the perpetration, planning, or preparation of, or participation in, terrorist acts or the providing or receiving of terrorist training.

3.2 Tax crimes

The Fourth Anti-Money Laundering Directive includes, in the definition of “criminal activity” which may give rise to money laundering, the following:

“All offences, including tax crimes relating to direct taxes and indirect taxes, (…) which are punishable by deprivation of liberty or a detention order for a maximum of more than one year or, as regards Member States that have a minimum threshold for offences in their legal system, all offences punishable by deprivation of liberty or a detention order for a minimum of more than six months”.

That provision was transposed into Luxembourg law by the Law of 23 December 2016, which introduces two new offences in the list of predicate offences relating to money laundering:

- aggravated tax fraud, which is defined according to the tax thresholds evaded or the level of reimbursement obtained;

- tax evasion, the increased gravity of which is due not only to the amounts involved but also to the fact that means have been employed with a view to deceiving the tax authorities.

The offences of aggravated tax fraud and tax evasion relate both to direct taxes (income taxes, registration fees, inheritance taxes, etc.) and to indirect taxes (VAT).

The offence of money laundering is punishable in respect of the predicate offences of aggravated tax fraud and tax evasion committed as from 1 January 2017.

CSSF Circular 17/650 contains in particular, in Annex I, a list of indicators likely to reveal potential laundering of a predicate tax offence, to which professionals may usefully refer. It should be noted that the presence of an indicator does not in itself justify any conclusion that a predicate tax offence has been committed. A new list of indicators specific to collective investment activities was introduced on July 3, 2020 in CSSF Circular 20/744 (see appendix 2).

Although professionals are not required to specify the predicate offence when lodging a suspicious operations report with the FIU (see Article 5 (1) (a) of the Law), they should be aware of the applicable thresholds needing to be exceeded for the purposes of commission of the predicate tax offences in question.

In the case of a customer resident in Luxembourg for tax purposes, the thresholds applicable to the offences in question are as follows:

“Any person who fraudulently evades or attempts to evade payment of all or any taxes, duties and levies the collection of which is the responsibility of the Administration de l’enregistrement et des domaines apart from value added tax shall, where the fraud thus committed or attempted relates, per reporting period or triggering event, to an amount exceeding one quarter of the duties due, being not less than 10 000 euros or an amount exceeding 200 000 euros, be liable to punishment, for aggravated tax fraud, in the form of imprisonment for a term of between one month and three years and a fine of between 25 000 euros and an amount equal to six times the amount of the duties evaded.

If the person concerned has systematically used fraudulent acts with a view to concealing pertinent facts from the tax authorities or persuading them that inaccurate information is correct, and if such committed or attempted fraud relates, per reporting period or triggering event, to a significant amount, either in absolute terms or in relation to the duties due, the perpetrator shall be liable to punishment, for tax evasion, in the form of imprisonment for a term of between one month and five years and a fine of between 25 000 euros and an amount equal to ten times the amount of the duties evaded.”

By contrast, the Luxembourg reporting thresholds are not applicable to non-residents, in respect of whom any potential suspicion should be reported, as the case may be, as from the very first euro, it being understood that the thresholds will vary depending on the customer’s tax residence.

However, money laundering is punishable in Luxembourg only if the offence is also a predicate offence in the country where the customer is resident, in accordance with the principle that the offence in question constitutes an offence in both countries.

4. From the original suspicion to the reporting of a suspicious operation

The obligation to cooperate with the authorities (Chapter 7) requires professionals to “inform the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) promptly, on their own initiative, (…) when they know, suspect or have reasonable grounds to suspect that money laundering, an associated predicate offence or terrorist financing is being committed or has been committed or attempted (…)”.

That obligation is such that the idea of a suspicion must exist as a precondition for proceeding, as the case may be, to submit a report to the FIU.

4.1 The notion of suspicion

The FIU defines suspicion as “(…) a negative opinion of someone or of his/her behaviour, based on hints, impressions, intuitions, but without any specific evidence. This means that, when reporting a suspicion, no evidence of money laundering, an associated predicate offence or terrorist financing is required. All that is needed are circumstances which would make such a hypothesis likely”.

“The terms ‘suspect’ or ‘have reasonable grounds for suspecting’ mean that the financial institution must treat the funds involved, the operation concerned or the act in question as suspect where, in accordance with its vigilance obligations and in light of its analysis of the information gathered by it, it is prompted to harbour a suspicion (‘suspect’), or where the circumstances include elements which do not allow it reasonably to dismiss all doubt (‘have reasonable grounds for suspecting’), regarding the lawfulness of the origin of the funds or of the operation, or regarding their economic, legal or fiscal justification”.

“The determination of the suspicion must be the fruit of a process of intellectual reasoning and duly substantiated analysis. It cannot be carried out by means of automated systems alone, but instead requires human intervention founded on an analysis of the atypical facts and operations and the circumstances thereof, in order to decide whether those atypical facts or operations are likely to be linked to money laundering/terrorist financing and must therefore be the subject of a report to the FIU or conversely to conclude, on the basis of that analysis, that such suspicions can be dismissed and that the matter is to be closed without any further action being taken.”

4.2 The origins of the suspicion

The professional may suspect, or have reasonable grounds for suspecting, that money laundering is going on, “(…) in particular in consideration of the person concerned, its development, the origin of the funds, or the purpose, nature and procedure of the operation”.

“(…) Reporting a suspicious transaction has no minimum monetary threshold. Several factors should be taken into account, which individually may seem irrelevant, but can generate doubts on the veracity of the operation when combined. In general, when a transaction or financial operation, whether only attempted or already executed, raises questions (from the professional) or raises a feeling of discomfort, worry or suspicion, it could potentially be linked to money laundering, an associated predicate offence or terrorism financing.”

It is best to use indicators that could reveal a possible link to money laundering, an associated predicate offence or terrorism financing. The report forms on goAML Web give three sets of indicators related (1) to the person of the customer or prospective customer, (2) to the operations or transactions, and (3) to the behaviour and profile of the customer or prospective customer.

4.3 Examples of suspected money laundering

The FIU has drawn up examples of indicators linked to the customer as a person, to an operation/transaction and to the customer’s behaviour/profile, relating to particular situations.

The indicators linked to the customer correspond, for example, to:

– criminal records or possession of the status of a PEP;

– suspicious or atypical behaviour;

– reluctance to hand over supporting documents;

– barely credible evidence of the origin of the customer’s assets;

– insistence on the speedy opening of an account.

Professionals are invited to draw up a list of non-exhaustive list of criteria which will give rise to suspicions on their part.

The indicators linked to an operation or transaction are multi-faceted.

“The suspicion can arise from the fact that the operation or transaction in question is the consequence of fraudulent behaviour, from the frequency of the transaction or operation, from the amount in question, from the unusual use of certain means of payment, from the interference of certain persons, natural or legal, from an act executed by a non-regulated financial intermediary, from the identity of the recipient of the funds or from the price used. The combination of several of these indicators increases the likelihood that money laundering, an associated predicate offence or terrorist financing is being committed.”

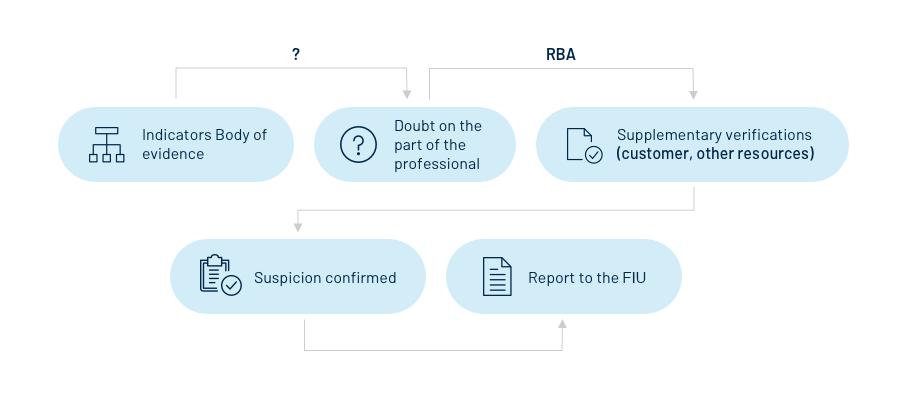

4.4 Summary of the reporting process

The process of submitting a report to the FIU may be summarised as follows:

The starting point of the period for reporting suspicious transactions to the financial intelligence unit begins as soon as the professional concludes that a residual doubt remains about the prospect / client or the transaction, confirming the suspicion. This is how the professional’s obligation to report “without delay” to the financial intelligence unit is understood.

If the professional considers, given the complexity of the case, that it will not be possible for him to complete his declaration in due form on time, it is recommended to proceed in two stages:

(i) by first sending the financial intelligence unit a short statement with enough elements to enable it to make a decision on a possible blocking

(ii) then an additional declaration to be made as soon as possible to provide additional information.

Exceptionally, in matters of terrorist financing, with regard to preventing a serious danger, the professional will contact the financial intelligence unit by telephone in parallel with the declaration by goAML.

Section 2. Risks linked with the cross-border transaction of banking and financial business

In the context of cross-border business, the legal classification of facts and acts as categorised under foreign laws, which may differ from that under Luxembourg law, may involve enhanced legal risks, notably of a criminal and regulatory nature.

“Member States should ensure that there are no obstacles to carrying out activities receiving mutual recognition in the same manner as in the home Member State, provided that the latter do not conflict with legal provisions protecting the general good in the host Member State.”

“(…) professionals, their dirigeants (executives) and employees are required, on their own initiative, promptly to provide information to the FIU (…)”

The obligation to report suspicious operations incumbent on an institution incorporated under foreign law operating pursuant to its freedom to provide services (FPS) in Luxembourg or via a Luxembourg branch is determined in accordance with Luxembourg law, which means that reports concerning suspected money laundering are to be submitted to the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU).

“(…) the notion of a professional also covers branches in Luxembourg of foreign professionals as well as professionals incorporated under foreign law providing services in Luxembourg without setting up a branch in Luxembourg.”

The cross-border transaction of banking business concerns two distinct situations:

- professionals established in Luxembourg exercising their freedom to provide services (“FPS”) in other European Union Member States;

- professionals established abroad operating on Luxembourg territory in the exercise of their FPS or having a branch in Luxembourg.

Professionals operating from Luxembourg in the exercise of their FPS are advised to acquaint themselves in advance of the statutory and regulatory provisions applicable in the territory of the host country/countries (being, inter alia, public order interest rules and overriding mandatory provisions) and their potential impact on the cross-border activities developed.

Professionals operating from or towards Luxembourg in the exercise of their FPS are bound not only to respect the rules designed to combat money laundering in their home country but also to take account of the criminal law and all general public interest rules in the host country.

Indeed, they could find that they are guilty of an offence against the rules laid down by the criminal anti-money laundering laws in the host country, and they must bear in mind that those laws, taken as a whole, encompass all behaviour likely to generate a profit, in so far as such behaviour contravenes the laws in question.

N.B. The Cour d’Appel, in its judgment of 3 June 2009, held that, “if necessary or appropriate in accordance with the second paragraph of Article 506-3 of the Penal Code, save in the case of offences for which the law allows a prosecution even though they are not punishable in the State where they have been committed, where the predicate offence has been committed abroad, whether or not it is punishable in the State where it has been committed, its categorisation depends on the Luxembourg law as applied by the court seised of the money laundering offence and not on the law of the State where it was committed”.

Professionals operating in the exercise of their FPS are invited to consult the list of supervisory authorities for the financial sector in the 28 Member States as drawn up by the European Banking Authority or the European Securities and Markets Authority.

They may also find it useful to refer to the dedicated sections contained in those authorities’ websites, compiling the relevant information regarding the legal framework in relation to financial crime, for example:

– the website of the Belgian FSMA;

– the website of the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority;

– the website of the German BAFIN

PERSONAL SCOPE OF APPLICATION

Section 1. Financial sector professionals operating in Luxembourg

The Law applies in particular to “credit institutions and financial sector professionals (FSPs) approved or authorised to carry on their activities in Luxembourg pursuant to the Law of 5 April 1993 on the financial sector as amended (…)”, payment institutions, electronic money institutions as well as “tied agents as defined in article 1 of the amended law of 5 April 1993 relating to the financial sector and agents as defined in article 1 of the law of 10 November 2009 on payment services established in Luxembourg ”.

The circle of persons subject to professional obligations in the combatting of money laundering and terrorist financing has now been extended to include all persons acting as family offices, persons carrying on, in Luxembourg, the activity of a provider of services to companies and fiducies, providers of gambling services and bailiffs.

The law of 25 March 2020 transposing the 5th Directive (EU) 2018/843 widened the list of subject professionals, in particular to providers of virtual asset services as well as custody or administration providers.

Section 2. Application of professional obligations to foreign subsidiaries and branches of professionals operating in Luxembourg

1. General principle

“Financial institutions should be required to implement programmes against money laundering and terrorist financing. Financial groups should be required to implement group-wide programmes against money laundering and terrorist financing, including policies and procedures for sharing information within the group for AML/CFT purposes. Financial institutions should be required to ensure that their foreign branches and majority-owned subsidiaries apply AML/CFT measures consistent with the home country requirements implementing the FATF Recommendations through the financial groups’ programmes against money laundering and terrorist financing.”

“Policies and procedures at group level:

Professionals forming part of a group are required to implement policies and procedures at group level, in particular data protection policies, as well as policies and procedures relating to the sharing of information within the group for the purposes of combatting money laundering and terrorist financing. Those policies and procedures must be implemented efficiently and in an appropriate manner, taking into account in particular the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing identified and the nature, particularities, size and activity of branches and subsidiaries, at the level of branches and subsidiaries in which a majority interest is held and which are established in Member States and third countries”.

“Group-wide policies and procedures include:

– the policies, controls and procedures provided for in Article 4, paragraphs (1) and (2);

– the provision, under the conditions of Article 5, paragraphs (5) and (6), of information from branches and subsidiaries relating to customers, accounts and operations, when necessary, for the purposes from the fight against money laundering and the financing of terrorism, to the functions of compliance, audit and the fight against money laundering and the financing of terrorism at group level. This covers data and analyzes of transactions or activities that appear unusual, if such analyzes have been carried out, and information related to suspicious statements or the fact that such a statement has been transmitted to the FIU. Likewise, when relevant and appropriate for risk management, branches and subsidiaries also receive this information from the group’s compliance functions; and

– adequate guarantees in terms of confidentiality and use of the information exchanged, including guarantees to prevent the disclosure of information “.

Directive (EU) 2013/34 on the annual financial statements, consolidated financial statements and related reports of certain types of undertakings defines the term “group” as : “a parent undertaking and all its subsidiary undertakings”.

As regards credit institutions and investment firms falling within the scope thereof, it will be noted that Regulation (EU) 575/2013 defines the terms “parent company”, “subsidiary” and “branch”.

Professionals will thus be required, in consultation with their subsidiaries/branches based abroad, to define a group policy to be implemented by those subsidiaries/branches, even where differences and/or specific national characteristics exist within the legal framework for combatting money laundering on the territories where those subsidiaries/branches are based.

In the implementation of that group policy, professionals must duly take account of the provisions concerning the “professional secrecy obligation” as referred to in Article 41 of the Law of 5 April 1993 on the financial sector.

Moreover, where an exchange of personal data involves a transfer of such data from a professional established in Luxembourg to an entity based in a third country which is not the subject of an adequacy decision of the European Commission, that data transfer may only be effected if it includes the “appropriate safeguards” referred to in Article 46 of the General Data Protection Regulation.

Thus, the professional must use, in particular, the legal instruments provided for to that end, such as binding corporate rules or the standard data protection clauses adopted by the European Commission, alternatively by a supervisory authority.

The law of March 25, 2020 introduced article 4-1, para I, point (b) in the Law allowing professionals of credit / financial institutions of Member States belonging to the same group to exchange information customers / accounts / transactions between group entities (including branches / subsidiaries majority owned and located in third countries), in this case only information necessary for AML purposes, especially those relating to transactions or activities unusual or the fact that a suspicious transaction report has been transmitted to the financial intelligence unit.

1.1 In a Member State

“Professionals operating establishments in another Member State shall ensure that those establishments respect the national provisions of that other Member State transposing Directive (EU) 2015/849.”

A branch/subsidiary established in another Member State must respect the national provisions of that host Member State transposing the Fourth Anti-Money Laundering Directive as amended.

1.2 “Abroad”: in a third State

“Professionals shall apply in their branches and majority-owned subsidiaries located abroad measures at least equivalent to those laid down in Directive (EU) 2015/849 or by the measures taken for their execution with regard to risk assessment, customer due diligence, keeping information and documents, adequate internal management and cooperation with the authorities.”

“Where the minimum standards on combatting money laundering and the financing of terrorism in a country where professionals have branches or majority-owned subsidiaries differ from those applicable in Luxembourg, those branches and subsidiaries shall apply the higher standard, to the extent that the laws and regulations of the host country so permit.”

“In this context, if the standards of the country in which these branches and subsidiaries are located are less strict than those provided for in Luxembourg, the data protection rules applicable in Luxembourg in the fight against money laundering and the financing of terrorism must be respected “, to the extent that the laws and regulations of the host country allow.

“Professionals shall pay particular to ensuring that this principle is complied with in respect of their branches and subsidiaries in high-risk countries.”

Thus, where the legal framework for combatting money laundering by a subsidiary or branch based in a third State features certain lacunae or is less strict than in Luxembourg, that subsidiary or branch based abroad must apply the Luxembourg rules in force.

The models and procedures concerning risk management, customer due diligence, cooperation with the authorities and with the FIU, retention of documents, internal controls, governance, the independent audit function and training must therefore be in compliance with the applicable Luxembourg rules in that regard, taking into account, moreover, the specific national characteristics peculiar to the State in which the branch or subsidiary is established.

2. Subsidiaries and branches established in third countries whose rules do not permit the application of equivalent measures

“Where a third country’s law does not permit the implementation of the policies and procedures required under paragraph 1, professionals shall ensure that their branches and majority-owned subsidiaries in that third country apply additional measures to effectively handle the risk of money laundering or terrorist financing, and inform the supervisory authorities and self-regulation bodies. If those additional measures are not sufficient, the supervisory authorities and self-regulation bodies shall implement additional supervisory measures, including requiring that the group does not establish, or that it terminates, business relationships, and does not undertake transactions and, where necessary, requesting the group to close down its operations in the third country concerned.”

This obligation is particularly relevant in respect of “higher-risk countries” as identified by the FATF.

“Institutions should ensure that their subsidiaries and branches take steps to ensure that their operations are compliant with local laws and regulations. If local laws and regulations hamper the application of stricter procedures and compliance systems implemented by the group, especially if they prevent the disclosure and exchange of necessary information between entities within the group, subsidiaries and branches should inform the compliance officer or the head of compliance of the consolidating institution.”

The fact that a third State does not authorise the subsidiary/branch of a Luxembourg professional to apply the Luxembourg anti-money laundering rules, even where additional measures to mitigate that prohibition are in place, may prompt that professional to regard itself as prohibited from carrying out transactions involving the subsidiary/branch established abroad

Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/758 (regulatory technical standards) allows professionals to refer to certain standards in the following contexts:

(1) individual risk assessments

(2) customer data sharing and processing

(3) disclosure of information related to suspicious transactions

(4) transfer and retention of data

2.1 Individual AML/CFT assessments

“Where the third country’s law prohibits or restricts the application of policies and procedures that are necessary to identify and assess adequately the money laundering and terrorist financing risk associated with a business relationship or occasional transaction due to restrictions on access to relevant customer and beneficial ownership information or restrictions on the use of such information for customer due diligence purposes”,

the professional must, at the very least:

- “inform the competent authority of the home Member State without undue delay and in any case no later than 28 calendar days after identifying the third country of the following:

- name of the third country concerned; and

- how the implementation of the third country’s law prohibits or restricts the application of policies and procedures that are necessary to identify and assess the money laundering and terrorist financing risk associated with a customer;

- ensure that [its] branches or majority-owned subsidiaries that are established in the third country determine whether consent from their customers and, where applicable, their customers’ beneficial owners, can be used to legally overcome restrictions or prohibitions referred to [above];

- ensure that [its] branches or majority-owned subsidiaries that are established in the third country require their customers and, where applicable, their customers’ beneficial owners, to give consent to overcome restrictions or prohibitions referred to [above] to the extent that this is compatible with the third country’s law.

Where the consent of the customer/beneficial owners is not feasible, credit institutions and financial institutions shall take additional measures as well as their standard anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism measures, to manage risk.”

- EXAMPLES OF ADDITIONAL MEASURES:

Article 3 of Delegated Regulation 2019/758 provides that at least two additional measures must be taken where necessary: the measure set out in point (c) of Article 8 and at least one of the measures set out in points (a), (b), (d), (e) and (f).

Accordingly, the following measure must be taken:

- carrying out enhanced reviews, including, where this is commensurate with the money laundering and terrorist financing risk associated with the operation of the branch or majority-owned subsidiary established in the third country, onsite checks or independent audits, to be satisfied that the branch or majority-owned subsidiary effectively identifies, assesses and manages the money laundering and terrorist financing risks.

That measure must be combined with at least one other pertinent measure, such as, for example:

- ensuring that its branches or majority-owned subsidiaries that are established in the third country seek the approval of the credit institution’s or financial institution’s senior management for the establishment and maintenance of higher-risk business relationships, or for carrying out a higher-risk occasional transaction;

- ensuring that its branches or majority-owned subsidiaries that are established in the third country restrict the nature and type of financial products and services provided by the branch or majority-owned subsidiary in the third country to those that present a low money laundering and terrorist financing risk and have a low impact on the group’s AML/CFT risk exposure;

- ensuring that its branches or majority-owned subsidiaries that are established in the third country carry out enhanced ongoing monitoring of the business relationship including enhanced transaction monitoring, until the branches or majority-owned subsidiaries are reasonably satisfied that they understand the money laundering and terrorist financing risk associated with the business relationship.

Where a credit institution or financial institution cannot effectively manage the money laundering and terrorist financing risk by applying the measures referred to above, it must:

- “ensure that the branch or majority-owned subsidiary terminates the business relationship;

- ensure that the branch or majority-owned subsidiary not carry out the occasional transaction;

- close down some or all of the operations provided by their branch and majority-owned subsidiary established in the third country”.

2.2 Customer data sharing and processing

The reader is referred to the Delegated Regulation, having regard to the prohibition of/restriction on sharing customers’ data imposed by the third State, and the measures prescribed in relation thereto, to be carried out within the group, are similar to those mentioned above.

In short, the professional must;

- inform the competent authority of its home Member State;

- where necessary obtain the consent of its customer/the beneficial owner(s) to the transmission of information; and

- if need be, take the requisite additional measures to overcome the problem in cases where such consent(s) cannot be obtained. Those additional measures include the ones referred to in points (a) and (c) of Article 8.

- where the risk of money laundering/terrorist financing is sufficiently high to necessitate other additional measures, credit institutions and financial institutions must apply one or more of the other additional measures mentioned in points (a) to (c) of Article 8.

2.3 Intra-group disclosure of information related to suspicious transactions

“The prohibition (of communication to the customer of the fact that information concerning him/her/it has been disclosed to the FIU) shall not apply to disclosure between credit institutions and financial institutions in Member States, provided they belong to the same group, or between those institutions and their branches and majority-owned subsidiaries located in third countries, on condition that those branches and majority-owned subsidiaries fully respect the policies and procedures defined at the level of the group, including procedures for sharing information within the group, in accordance with Article 4-1 or Article 45 of Directive (EU) 2015/849, and that the group-wide policies and procedures comply with the requirements laid down in this Law or in Directive (EU) 2015/849”.

This exception is to be strictly construed, in that it is applicable only in an intra-group context.

“For professionals who are part of a group, they are required to include in their group-wide policies and procedures, the policies, controls and procedures required (by the Act) and the provision (…) of information from branches and subsidiaries relating to customers, accounts and transactions, where necessary for AML/CFT purposes, to the compliance, audit and AML/CFT functions at group level.

This includes data and analyses of transactions or activities that appear unusual, if such analyses have been carried out, and information relating to suspicious reports or the fact that such a report has been forwarded to the FIU.

Similarly, where relevant and appropriate for risk management purposes, branches and subsidiaries also receive such information from the group compliance functions. Adequate safeguards for the confidentiality and use of the information exchanged, including safeguards to prevent disclosure of information, should be provided.”

“Information on suspicions that funds are the proceeds of money laundering or of an associated predicate offence, or are related to terrorist financing, reported to the Financial Intelligence Unit shall be shared within the group, unless otherwise instructed by the Financial Intelligence Unit.”

2.4 Transfer of customer data to the Member States in the context of AML/CFT supervision

“Where the third country’s law prohibits or restricts the transfer of data related to customers of a branch or majority-owned subsidiary established in a third country to a Member State for the purpose of supervision for anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism, (…)”, the professional must at least inform the competent authority of the home country as indicated in point 2.1 above.

The professional must, in addition, at least:

- carry out enhanced reviews, on-site checks or independent audits of the branch or majority-owned subsidiary established in the third country;

- require the branch or majority-owned subsidiary established in the third country regularly to provide relevant information to the credit institution’s or financial institution’s senior management, including:

- the number of high-risk customers;

- the number of suspicious transactions identified and reported;

- make the information available to the competent authority of the home Member State upon request.

RISK BASED APPROACH

1There exist three levels of risk assessment:

- a supranational risk assessment at European level, the results of which were published by the European Commission on 26 June 2017, updated on 24 July 2019.

- a national risk assessment to be carried out by each Member State with a view to evaluating the level of risk attaching to activities carried out in its territory.

Luxembourg updated its national risk assessment concerning money laundering and terrorist financing on 15 December 2020. A concise summary of the national risk assessment is made available to professionals.

“Each Member State shall make appropriate information available promptly to obliged entities to facilitate the carrying-out of their own money laundering and terrorist financing risk assessments”:

- Identification, assessment and proper understanding by the professional itself of the risks it faces, which must enable the latter to determine which due diligence measures will be applied to the business relationship on the basis of the materiality of the risk.

“To this end, the professional must integrate different sources into his risk management procedures, including:

- The supranational report of the European Commission on the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing (“Supra National Risk Assessment”);

- The national risk assessment for money laundering and terrorist financing (“National Risk Assessment”);

- Sub-sector ML / FT risk assessments (“sub-sector Risk Assessments”);

- The Joint Guidelines issued by the 3 European supervisory authorities (ESMA, EBA and EIOPA) on money laundering and terrorist financing risk factors (“Risk factor Joint Guidelines”);

- Relevant CSSF publications ”.

(see below, “The obligation to carry out a risk assessment”).

The risk-based approach cannot be dissociated from the notion of “risk appetite” in the combatting of money laundering.

Risk appetite should at least take into consideration factors such as the business carried on, the target clientele and undesirable customers, the geographical countries/areas concerned, and prohibited structures (…).

“The professional’s determination of his risk-based approach is necessarily based on the definition of ML / FT risk appetite, as approved by the board of directors and transposed by authorized management.

The strategy must be consistent with this approach. The AML / CFT policies, procedures and controls put in place within the professional must be consistent with the appetite for the previously defined risk. This definition and strategy must be communicated in a precise, clear and understandable manner to all the personnel concerned “.

Section 1. Identification and assessment of risks

“(…) Countries should identify, assess, and understand the money laundering and terrorist financing risks for the country, and should take action (…) and apply resources, aimed at ensuring the risks are mitigated effectively. Based on that assessment, countries should apply a risk-based approach (RBA) to ensure that measures to prevent or mitigate money laundering and terrorist financing are commensurate with the risks identified.” This recommendation was updated by the FATF in November 2020 for professionals to identify, assess and mitigate the risks of potential breaches of non-application or bypassing of financial sanctions relating to proliferation financing.

Both the Law and CSSF Regulation n ° 12-02 require professionals to identify and assess the money laundering and terrorist financing risks to which they are exposed.

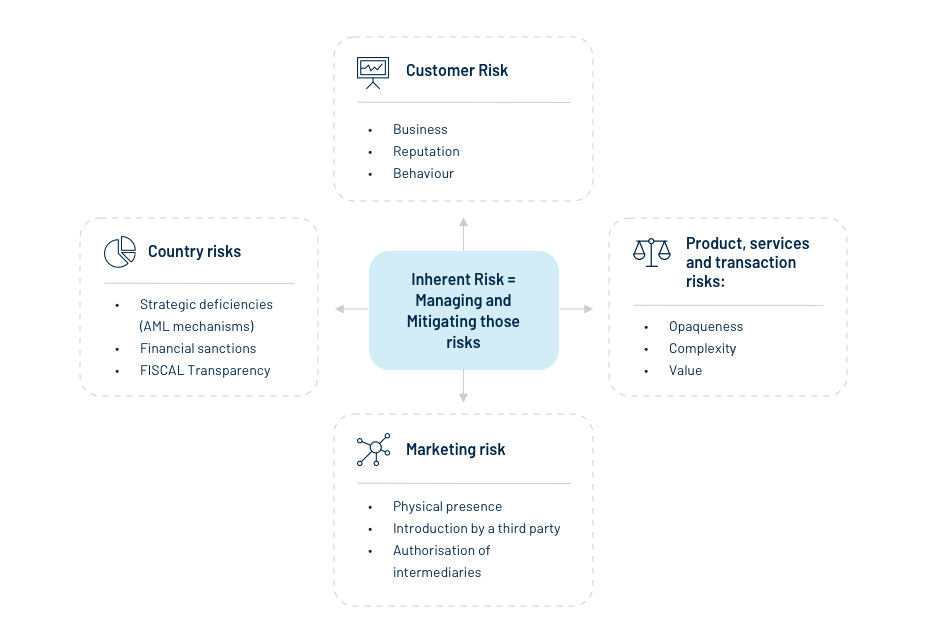

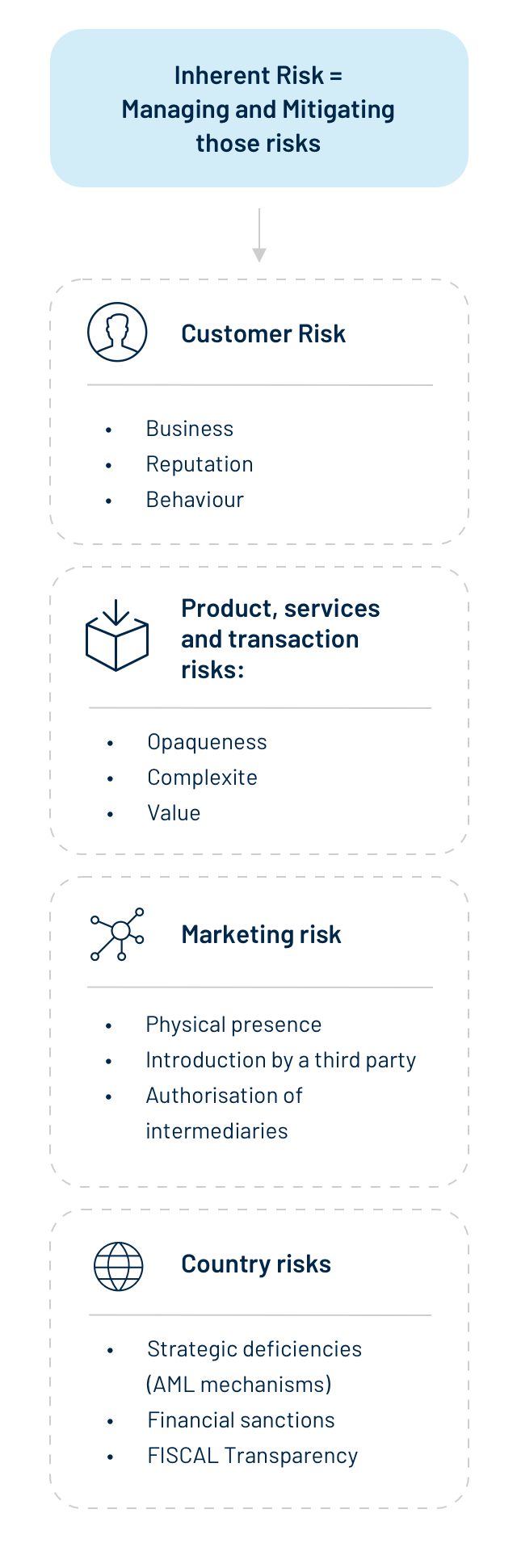

In addition to the professional’s obligation to assess the overall risk in relation to his activity, he also classifies individual risks concerning his business relationships.

The professional classifies all of his clientele according to a coherent combination of risk factors.

“Besides those cases where the risk level is to be considered as high pursuant to the Law or the Grand-Ducal Regulation, that level shall be assessed according to a consistent combination of risk factors defined by each professional according to the activity exercised and inherent to the following risk categories:

– type of customers (including client, agent, beneficial owner);

– countries and geographic areas;

– products, services, transactions or;

– distribution channels.”

“Professionals determine the scope of due diligence measures (with regard to customers) according to their assessment of the risks associated with the types of customers, countries or geographical areas and with particular products, services, transactions or distribution channels”.

The Law draws a clear distinction between, on the one hand, the obligation to carry out an assessment of the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing which the institution concerned faces by virtue of the business areas in which it engages and, on the other hand, the obligation to apply due diligence measures in relation to its customers, the extent of which will depend on the assessment of the risks regarding each customer or prospective customer.

See Part 2, Chapter 1 : “Obligations vis à vis customers”

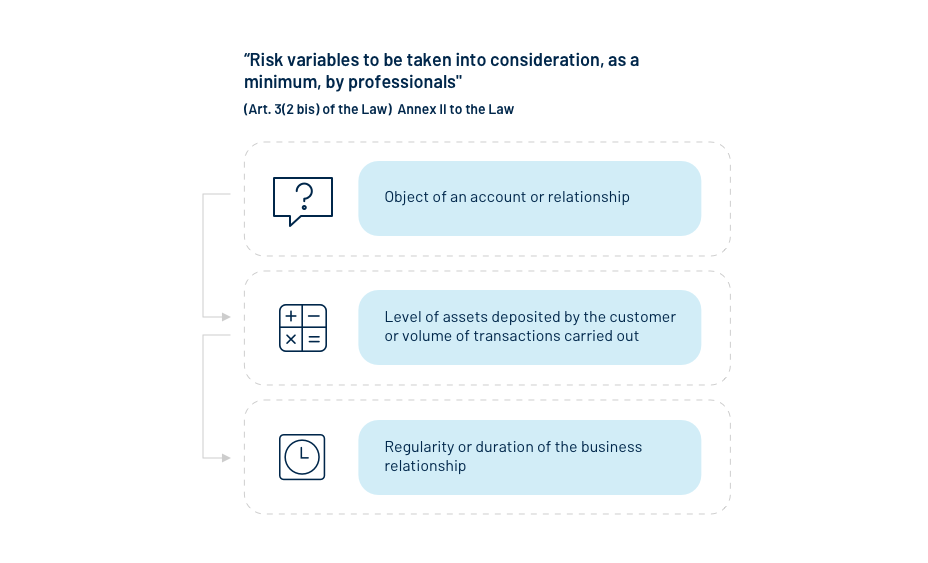

“(1) Professionals shall take appropriate steps to identify, assess and understand the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing that they face, taking into account risk factors including those relating to their customers, countries or geographic areas, products, services, transactions or distribution channels. Those steps shall be proportionate to the nature and size of the professionals.”

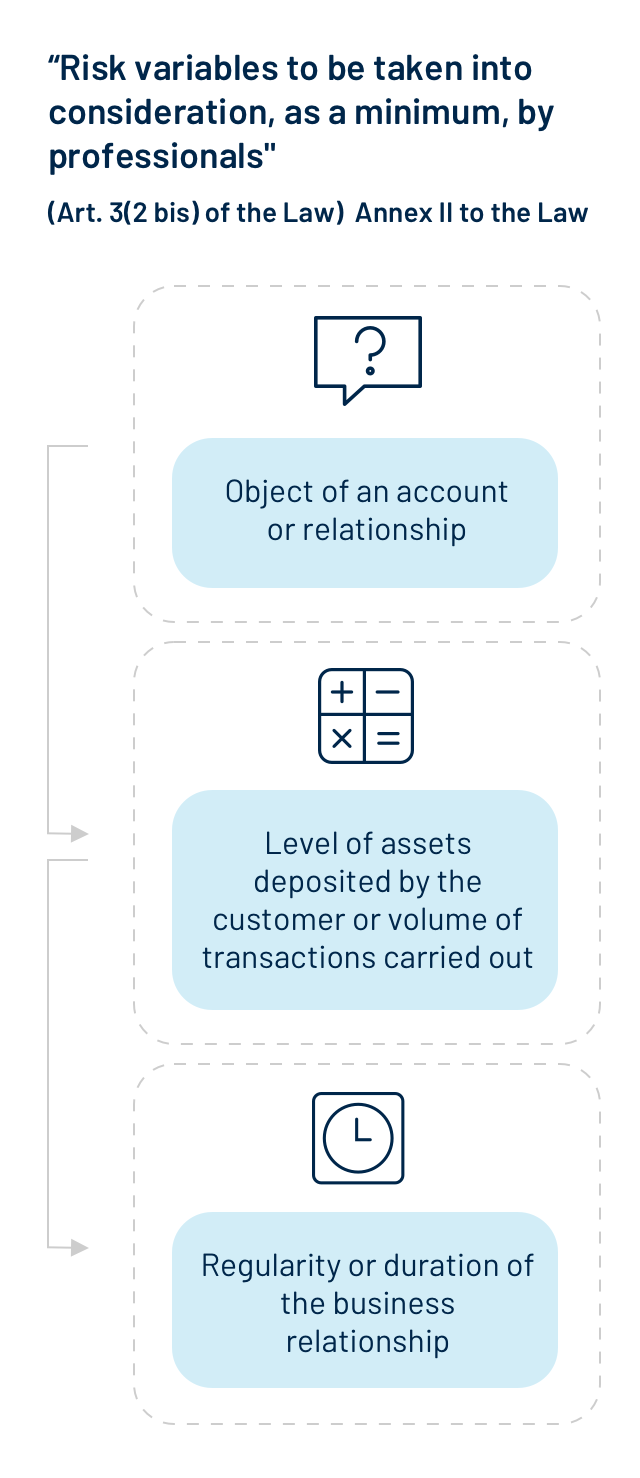

That article is accompanied by three annexes (II to IV) in the Law, setting out, first, a non-exhaustive list of the risk variables which professionals should automatically take into consideration, followed by two lists of factors/elements indicative of a potentially lower risk and a potentially higher one.

“(2) Professionals consider all relevant risk factors before determining the overall risk level and the level and type of appropriate measures to apply to manage and mitigate those risks. Professionals also ensure that the risk information contained in the national and supranational risk assessment or communicated by supervisory authorities, self-regulatory bodies or European supervisory authorities is included in their risk assessment.

Professionals shall document, keep up-to-date and make the risk assessments referred to in paragraph 1 available to the supervisory authorities and self-regulation bodies. The supervisory authorities and self-regulation bodies may decide that individual documented risk assessments are not required where the specific risks inherent in the sector are clear and understood.

(3) Professionals shall identify and assess the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing which may result from the development of new products and business practices, including new

distribution mechanisms, and the use of new or developing technologies related to new or pre-existing products.

Professionals shall: (a) assess the risks before the launch or use of these products, practices and technologies; and (b) take appropriate measures to manage and mitigate those risks.

THE OBLIGATION TO CARRY OUT A RISK ASSESSMENT

Subsection 1. Factors and elements indicative of a potentially higher risk as referred to in Article 3-2 (I), second subparagraph of the Law:

The specific risks listed here are discussed in greater detail later on in this Handbook, in dedicated sections dealing with the different sectors of activity.

Professionals will take note, in particular, of a potentially higher risk in the cases referred to below:

1.1 Risk factors inherent in customers

- business relationships occurring in unusual circumstances;

- customers residing in high-risk geographical areas (…);

- legal persons or legal arrangements which are structures for holding personal assets;

- companies whose capital is held by nominee shareholders or represented by bearer shares;

- activities necessitating large amounts of cash;

- companies whose ownership structure appears unusual or inordinately complex, having regard to the nature of their business;

- the customer is a third country national who applies for residence rights or citizenship in the Member State in exchange for capital transfers, purchase of property or government bonds, or investment in corporate entities in that Member State.

On 17 October 2018 , the OECD published Recommendations concerning lists of programmes of residence and citizenship that can be obtained by investment (“Citizenship by Investment” and “Residence by Investment”) which may pose a high risk to the integrity of the Common Reporting Standard (CRS).

According to the OECD, financial institutions are required to take that list duly into account when performing their due diligence obligations in relation to fiscal transparency.

Those programmes may also be misused to conceal offshore assets by circumventing the reporting obligation under the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard.

In addition to the higher-risk factors inherent in certain customers, professionals must invariably take full account of the risk variables mentioned below in relation to their customers:

“Professionals take into consideration, in their assessment of the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing, linked to the types of customers, to the countries and geographical areas and to the specific products, services, operations or distribution channels, the risk variables linked to these risk categories. These variables, taken into account individually or in combination, can increase or decrease the potential risk and, consequently, have an impact on the appropriate level of due diligence measures to be implemented ”.

In short, the risk factors are linked to the customer himself, in light of his behaviour and of any unusual circumstances characterising the business relationship.

In some cases, the professional will be unable to agree to enter into a business relationship with a customer, either because this is prohibited by law or because the risks inherent in the customer are too high, in particular:

– where the customer appears on an official list or lists of persons/entities/groups subject to restrictive measures in financial matters in the context of combating terrorist financing;

– where the nature of the activities carried on by the customer represents an excessively high risk which cannot be mitigated or which does not correspond to the risk policy previously defined by the professional;

– where the professional is unable to offer the product/service requested by the prospective customer (e.g. acting as the custodian bank for virtual currencies, or providing a money remittance service);

– where the professional finds that the prospective customer is unable to provide the requisite guarantees, as determined by the professional concerned, evidencing fiscal transparency/conformity;

– where the professional finds that the documentation enabling it to comprehend the structure of a company/chain of companies or the economic justification for a financial arrangement is insufficient;

– any other circumstance rendering it impossible to dispel any doubts existing in the mind of the professional.

1.2 Risk factors linked to products/services/transactions/distribution channels

(a) private banking

Private banking, or more precisely the management of assets “consisting in the provision of banking services and other financial services to high-net-worth individuals”, is cited as a high-risk factor. According to the European Banking Authority (EBA), the presence of this activity amongst the risk factors is due to the risk of tax evasion. The EBA states that “wealth management firms’ services may be particularly vulnerable to abuse on the part of customers who wish to conceal the origin of their funds or, for example, evade tax in their home jurisdiction.”

In the opinion of the Joint Committee of the European Supervisory Authorities, private banking/wealth management gives rise to “a potentially higher risk”. Professionals must assess in each case the risks relating to the customer, taking into consideration a series of risk criteria or circumstances peculiar to the business relationship.

Summary (in French) of the national money laundering risk assessment [/ left-bookmark]Thus, different risk factors exist, depending on the profile of the customer wishing to enter into a business relationship.

The National Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Risk Assessment 2020 notes that private banking is particularly exposed to money laundering risks, in particular for the complexity of certain products such as asset structuring activities.

(b) products or transactions that might favour anonymity;

(c) non-face-to-face business relationships or transactions, without certain safeguards, such as electronic identification means, relevant trust services within the meaning of Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 or any other secure, electronic or remote identification process, regulated, recognized, approved or accepted by the authorities national concerned;

(d) payments received from unknown or unassociated third parties;

(e) new products and new business practices, including new delivery mechanisms, and the use of new or developing technologies for both new and pre-existing products;

(f) transactions related to oil, arms, precious metals, tobacco products, cultural artefacts and other items of archaeological, historical, cultural and religious importance, or of rare scientific value, as well as ivory and protected species”.

1.3 Geographical risk factors

The factors/elements indicative of a potentially higher risk are as follows:

“(a) (…) countries identified by credible sources, such as mutual evaluations, detailed assessment reports or published follow-up reports, as not having effective anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing systems;

(see for example the mutual evaluations or assessment reports of the FATF)

(b) countries identified by credible sources as presenting significant levels of corruption or other criminal activity (see for example the list of countries (corruption) published by Transparency International);

(c) countries the subject of sanctions, embargoes or other similar measures imposed by, for example, the European Union or the United Nations (see the list of sanctions of the Security Council of the United Nations);

(d) countries financing or supporting terrorist activities or that have designated terrorist organisations operating within their territory”.

“The supervisory authorities and self-regulatory bodies provide professionals with information on countries which do not apply or insufficiently apply measures to combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism and in particular on the concerns raised by the failures of anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing systems in the countries concerned.

The supervisory authorities may require credit and financial institutions to adopt one or more enhanced due diligence measures proportionate to the risks (…), in the context of business relationships and transactions with natural persons or legal entities involving such countries ”.

In addition to the above, professionals should draw up a list of countries posing a high risk of money laundering or terrorist financing.

In practice, professionals usually draw up lists classifying countries in different categories: low risk, medium risk high risk. Certain countries may present risks regarded as unacceptable by certain institutions.

Annex III provides professionals with relevant links relating inter alia to lists of countries subject to prohibitions and restrictive measures in financial matters and third countries presenting a low risk of corruption/terrorist financing.

The professional will ensure that the instructions published by the CSSF are complied with, if applicable.

1.4 International financial sanctions

A) Essentials on International Financial Sanctions

Financial sanctions are restrictive measures in financial matters, taken against certain States, natural or legal persons, entities and groups about a change of policy (domestic or foreign) or activity on the part of the States or persons designated.

The Ministry of Finance is competent to deal with all questions relating to the implementation of financial sanctions raised both by those at whom those measures are targeted and those who are called upon to apply them. Accordingly, professionals shall inform the Ministry of Finance of the enforcement of each restrictive measure (including attempted transactions) taken in respect of a State, natural or legal person, entity or group designated according to the Law of 19 December 2020 on the implementation of restrictive measures in financial matters.

In the same vein, professionals who have reported a case of sanction to the Ministry of Finance shall simultaneously address to the CSSF a copy of this report.

The CSSF remains the competent supervisory authority, which will verify professionals’ compliance with the Law on financial restrictive measures. Consequently, the CSSF will be able to apply administrative sanctions to professionals, which would fail implementing appropriate procedures/processes in this regard.

Any notification to the Ministry of Finance and associated with restrictive measures shall be made without prejudice for professionals to make, as the case may be, suspicious activity/transaction reports to the Financial Intelligence Unit.

WHAT TO DO?

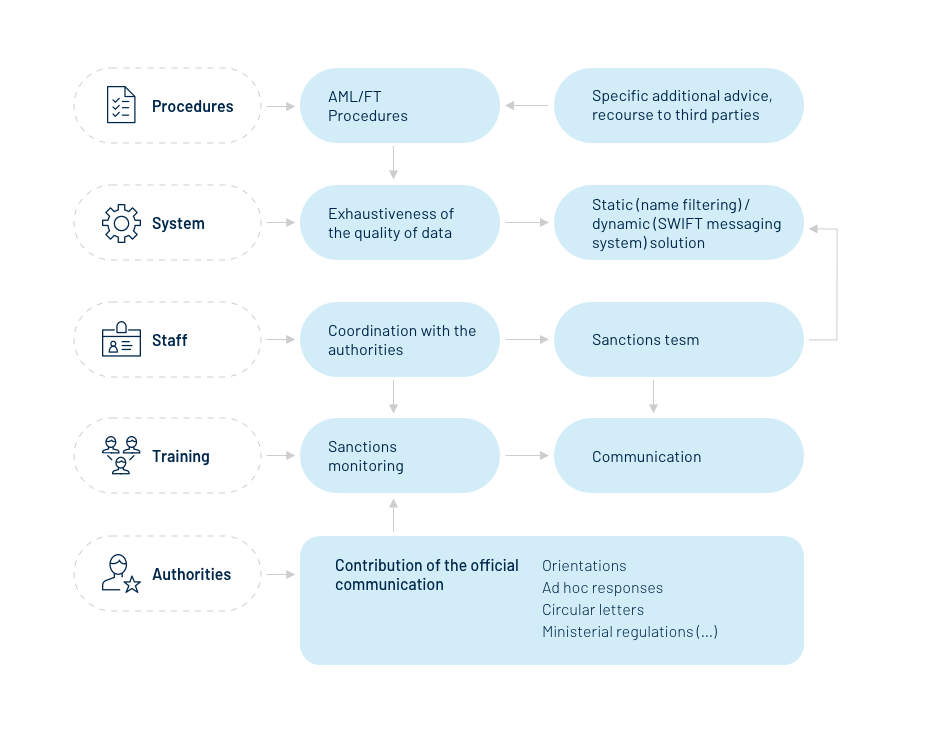

In order to avoid the eventuality that a customer or prospective customer may be subject to international sanctions, professionals must have in place stringent procedures for identifying persons and monitoring transactions involving, in particular, technical resources/filtering systems based on lists of international sanctions (filtering of names, transactions and the SWIFT messaging system).

In the specific context of combatting terrorist financing and proliferation financing, banks must take into consideration, in particular:

– the Law of 19 December 2020 relating to the implementation of restrictive measures in financial matters.

The Law of 19 December 2020 repealed the law of 27 October 2010 and implements in Luxembourg the restrictive measures in financial matters adopted against certain States, natural and legal persons, entities and groups by the provisions of the resolutions adopted by the Security Council of Nations and certain acts of the European Union.

– the list of sanctions of the Office of Foreign Assets Control (United States of America) in so far as these have extra-territorial scope;

The aforementioned procedures shall cover the customer due diligence measures set out in the Law, encompassing the identification of the customers/beneficial owners but also the scrutiny/monitoring of transactions throughout the course of the customers’ relationships, ”without delay”, to ensure that funds will not be made available to States, persons, entities and groups subject to restrictive measures in financial matters.

As soon as a case of sanction is spotted, professionals should not hesitate to escalate it without delay to the Ministry of Finance and provide it with all necessary information linked to the case at hand.

The reporting of cases of sanctions to the Ministry goes hand in hand with the hard blocking of the account (cash & financial instruments) without delay, the latter being an obligation of result. Indeed, professionals shall apply without delay the required restrictive measures, hence proceed to the freezing of funds owned by the listed person.

The reporting made to the Ministry of Finance shall yet not be confused with a suspicious transaction/activity reporting made to the Financial Intelligence Unit.

Indeed, the “no-tipping off” rule obligates professionals not to inform their customers/prospects on the fact that their accounts are blocked, whereas such rule would not apply to restrictive measures in the event that no STRs/SARs were made. The list of sanctions being publicly available, customers under financial restrictive measures could eventually be informed on the fact that their accounts are frozen.

The consequences of failure to take into consideration persons/groups/entities/countries featuring in particular on those lists may considerably impact the activities carried on, and the services provided, abroad by the professional (criminal prosecutions, administrative penalties, reputation risks, substantial fines, and/or suspension/withdrawal of an authorisation or licence).

The ABBL recommends that professionals should regularly check the list of resolutions of the Security Council of the United Nations and to sign up free of charge to the Financial Sanctions Newsletter published by the Ministry of Finance. Professionals may also consult and sign up for the consolidated list of sanctions imposed by the European Union. The Ministry of Finance also provide useful tools to help professionals keep up with processing international financial sanctions. So does the CSSF with its website dedicated to international financial sanctions.

The ABBL also recommends that professionals opt to put in place an internal system possibly resembling the one illustrated below:

The European Commission stated in an opinion of 7 June 2019 that all funds and economic resources belonging to the entities listed in Annex VI of Regulation 2016/44 include interest, dividends or other incomes from assets or capital gains stemming from frozen assets.

WHAT TO DO … when the professional conducts its research?

As regards measures to freeze assets, any indications relating to pseudonyms which feature in the ID information may be taken into account, depending on their reliability. The professional must conduct its research working on the basis of reliable pseudonyms, that is to say, high-value pseudonyms considered to be of great significance for identification purposes

Unreliable pseudonyms, that is to say, low-value pseudonyms considered to be of minor importance for identification purposes, help economic operators and other actors to confirm the ID of persons at whom sanctions are targeted.

A professional may be confronted with a homonymy situation, where the surname and first name of a prospective customer are the same as those of a person listed, including where the surname is not distinguishable from the first name.

In cases of homonymy, the accounts must be closely watched and movements must be suspended. The Ministry of Finance must be alerted so that it can decide on the situation.

The fact that the surname and first name of the person concerned are the same as those of a listed person is not enough to justify concluding that the case involves one and the same person. On the contrary, there may be other information showing very clearly that it involves quite different persons. For example, such information may reveal a different geographical location, different posts and occupations, different dates of birth and/or different passport numbers.

Professionals confronted with possible cases of homonymy must seek further information before taking any decision, and must keep a written record of the results of their research. If that information, taken as a whole, manifestly shows that another person is involved, it will not be necessary or appropriate to contact the Ministry of Finance.

Where there is any doubt or if the homonymy research proves unconclusive,, the professional should contact the Ministry of Finance and suspend movements on the account(s) concerned (cash and financial instruments) pending final clarification. The availability of a limited number of pieces of information will not by itself justify the pursuit of an operation.

B) Specific clarifications related to national/international financial sanctions regime

SCREENING SCOPE of CSSF Regulation 12-02:

Professionals should implement control mechanisms that allow them, when accepting customers or monitoring the business relationships, to identify, among others:

- the persons as referred to in Articles 30, 31 and 33 of the regulation;

- the funds coming from or going to States, persons, entities or groups as referred to in Article 33 of this regulation (…)”

The name screening has to include all the accounts of customers and their transactions and shall apply to customers, proxies, initiators and beneficial owners as well as, as regards the supervision of transfers of funds, to the payer of an incoming transfer of funds and the recipient of a transfer of funds going out of the customer’s account.

Remember:

The screening scope is not subject to the risk-based approach enshrined in the Law and cannot be invoked/used by professionals when applying sanctions screening.

The identification researches carried out shall be duly documented, including in cases where there are no positive results.

Professionals also have the obligation to identify the States, persons, entities and groups subject to restrictive measures in financial matters also with respect to the assets they manage and to ensure that the funds will not be made available to these States, persons, entities or groups.

SCREENING TIMING & SCREENING FREQUENCE

Professionals have to carry out a name screening :

- before establishing a new business relationship

- before carrying out wire transfers by debit of customer account or before crediting incoming funds to customer accounts;

- on longstanding business relationships.

In its annual activity report of 2014, the CSSF stated that « Controls such as “name matching”, i.e. controls on the client database performed in relation to:

- acts directly applicable in Luxembourg, as adopted by the EU (in particular, EU regulations) and including prohibitions and restrictive financial measures against certain persons, entities or groups respectively i. in the context of the fight against terrorist financing or ii. in the context of other financial embargoes; and

- national regulatory texts concerning financial sanctions relating to the fight against terrorist financing based (on the law of 27 October 2010) implementing the United Nations Security Council resolutions (and Grand-ducal Regulation of 29 October 2010) enforcing the aforementioned law

« must be performed without delay after the publication of each new amendment ».

Such controls are independent from any other frequency of controls, of whatever type (for example, in relation to the detection of PEPs), which may have been put in place by the professional ».

“Without delay” means, in the context of the implementation of the financial sanctions, including the freeze of assets or other economic resources or other restrictive measures taken in application of the above-mentioned texts :

« a delay of, ideally, a few hours following the publication of the measures by the CSSF and/or the Ministry of Finance ». In any case, it should be interpreted in relation to the need to prevent the outflow or the dispersion of funds or other goods linked to the designated persons, entities and groups.

WHAT TO DO?

Professionals must ensure that their screening tools are updated without any delay with the names of newly designated or de-listed persons or entities after the publication of the measures by the CSSF and/or the Ministry of Finance.

Professionals must also carry out a name screening on longstanding business relationships without any delay after the publication of the measures by the CSSF and/or the Ministry of Finance and to take into account the amendments also when entering new business relationships or executing in/out wire transfers.

1.5 Risks surrounding Virtual Assets (a.k.a. crypto assets) and Virtual Asset Service Providers

Overview

In the current ecosystem of growing cross-border/digital transactions and the rapid rise of trades involving crypto assets, there is a need to understand and mitigate the ML/TF risks associated with crypto asset providers/activities. The 2018 and 2020 Luxembourg national risk assessments highlighted virtual assets (“VAs”) as one of the key emerging and evolving risks of ML/TF.

Banks are exposed to risks stemming from VAs as they are the point of contact of centralised exchange users with the traditional finance sector. Criminals using VAs for ML/TF activities need to convert VAs to fiat, or vice-versa. For these purposes, criminals use exchanges, the deposits and withdrawals from which are usually done to and from bank accounts.

Credit institutions are exposed to the risks arising from virtual currencies (“VAs”) mainly in circumstances where customers of regulated credit and financial institutions deal in VAs or where they are VASPs. The main factors contributing to the increased exposure to the ML/TF risks is the limited transparency of VAs transactions and the identities of the individuals involved in these transactions.

The FATF indeed draws attention to the top two threats related to the VAs risk landscape:

- The continued use of of tools and methods to increase the anonymity of VAs transactions putting at risk the “travel rule” (i.e., identification of the originators and beneficiaries of VA transactions), hence potentially the KYC procedures set-up by VASPs;

- VASPs registered or operating in jurisdictions that lack effective AML/CFT regulation, possibly revealing weak AML/CFT systems and procedures.

Definitions

Professionals may be involved in VAs activities or even act as Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASPs).

A virtual asset is “a digital representation of value, including a virtual currency, that can be digitally traded, or transferred, and can be used for payment or investment purposes, except for virtual assets that fulfil the conditions of electronic money and the virtual assets that fulfil the conditions of financial instruments”.

A VASP is any person providing, on behalf of or for its customer, one or more of the following services:

(a) the exchange between virtual assets and fiat currencies, including the service of exchange between virtual currencies and fiat currencies;

(b) the exchange between one or more forms of virtual assets;

(c) the transfer of virtual assets;

(d) the safekeeping or administration of virtual assets or instruments enabling control over virtual assets, including the custodian wallet service;

(e) the participation in and provision of financial services related to an issuer’s offer or sale of a virtual asset

Understanding VAs and VASPs

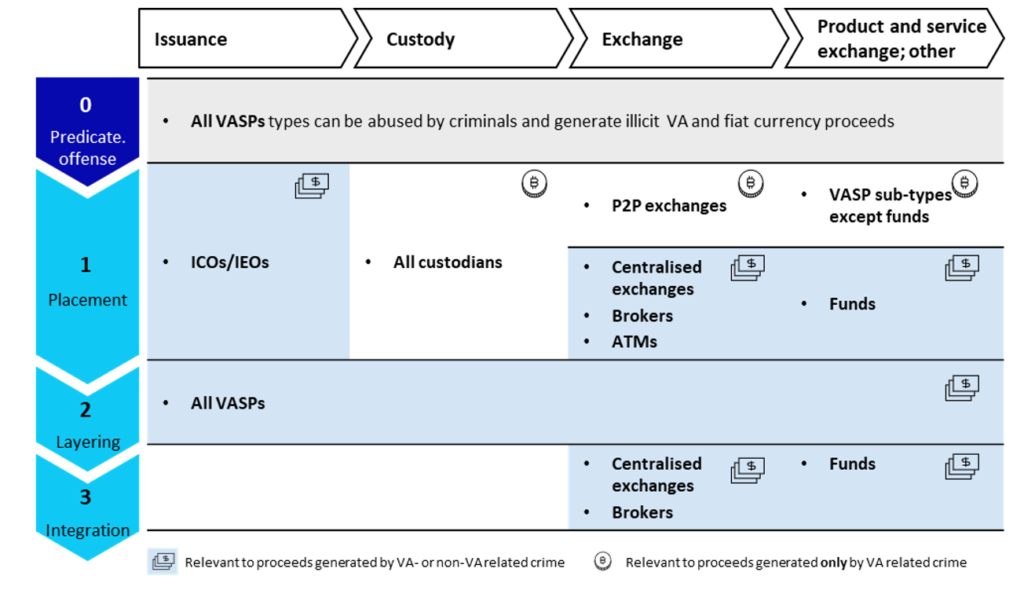

For financial institutions to better apprehend the ML/TF risks of their VASPs customers, it is necessary to briefly understand the ML/TF risks the latter must deal with. VASPs’ exposure to ML/TF threats is due to multiple factors, to the extent that those financial institutions are exposed to:

- Non-face-to-face business relationships

- International nature of business

- High volume of transactions

- Technological complexities of VAs/VASPs

- Anonymous properties of VAs

- High volatility and complex valuation of VAs

Potential exposure of VASPs at each ML/TF step:

Mitigation of risks (overall)

WHAT TO DO